Archbishop Ngô Đình Thục

Born in 1897, Peter Martin Ngo Dinh Thục was a prominent member of the Ngo family regime of South Vietnam, which came to power in 1955 with backing from the U.S. government and CIA. The Ngo regime ended with the Buddhist Crisis of 1963 and the assassination of Thục's brothers, President Ngo Dinh Diem and his advisor Ngo Dinh Nhu. Thục's assets in Vietnam were seized on December 25, 1963. On November 11, 1964, Pope Paul VI removed Thục from control of the Archdiocese of Hue, replacing him with Bishop Philippe Nguyen Kim Dien.

Thục reached international prominence during the fall/winter of 1963, until he was silenced by Paul VI in 1968 and stripped of administrative authority. After the Fall of Saigon in 1975, facing obscurity and financial difficulties, Thục began consecrating various individuals from 1975 to 1981 in Spain and France.

Administrative Approach to Abuse Cases

In his memoirs, published in the German sedevacantist magazine Einsicht in August 1982, Thục described his administrative approach to handling sexual abuse cases during his tenure as bishop in Vietnam. As documented in Sede Vacante by Jarvis (2018), p. 36:

"I would reprimand him on the basis of spiritual reasons: offense to God, sacrilege for Masses said in a state of mortal sin, scandal, ineffective ministry; without showing anger, but with great compassion. Finally, I would ask him to suggest the spiritual punishment incurred: for example a one-week spiritual retreat, or a month in a monastery, or a change of post. I can only congratulate myself for this way of handling things."

Political and Ecclesiastical Career

Thục was consecrated as the third Catholic bishop of Vietnam in 1938 and appointed Archbishop of Hue in 1960 by Pope John XXIII. The U.S. government initially supported the Ngo family but later determined that their oppression of Buddhists was counterproductive. The CIA subsequently assisted in staging a coup that removed the Ngo family from power, contributing to the events that led to the Vietnam War.

Thục was attending the Second Vatican Council in Rome in 1963 and never returned to Vietnam after his family was removed from power. In 1963, he made a visit to the United States to meet with Cardinal Spellman and Bishop Fulton Sheen.

During Vatican II, Thục was sometimes ruled out of order for demanding that non-Christians be allowed as observers at the council, and he was considered one of the more liberal participants. AP reported that on March 30, 1968, Pope Paul VI removed Thục from all authority over the Archdiocese of Hue, replacing him with Archbishop Philippe Nguyen Kim Dien. After 1968, Thục retained only a titular position as Archbishop of Bulla Regia (Souk-el-Arba, Tunisia).

From 1963 until 1975, limited information is available about Thục's activities. His life from 1975 until his death in 1984 involved various episcopal consecrations that became the focus of sedevacantist organizations.

Scholarly Resources

External scholarly perspectives on Archbishop Thục, the Ngo family regime, and the Palmarian Church include:

- Sede Vacante: The Life and Legacy of Archbishop Thuc by Edward Jarvis, published in 2018 by Apocryphile Press (publisher page)

- The Sacred and The Profane by Clarence Kelly (SSPV), Seminary Press, 1997 (direct download)

- A Pope of their Own (Second Edition) by Magnus Lundberg, published in 2020 by Uppsala University (direct download)

- Misalliance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and the Fate of South Vietnam by Edward Miller, published in 2013 by Harvard University Press (publisher page)

- Background to Betrayal: The Tragedy of Vietnam by Hilaire Du Berrier, published in 1965 by Western Islands (archive.org)

- CIA and the House of Ngo by Thomas L. Ahern, Jr. Written by the CIA in 2000 and declassified in 2009 (direct download) or (download from CIA website)

CMRI Connection Summary

Bishop Mark Pivarunas was consecrated by Bishop Moisés Carmona in 1991, who had been consecrated by Archbishop Thục in 1981 (when Thục was 84 years old). All current CMRI priests derive their authority through the Thục episcopal lineage. Traditionalist Catholics have debated the validity and legitimacy of these consecrations for decades.

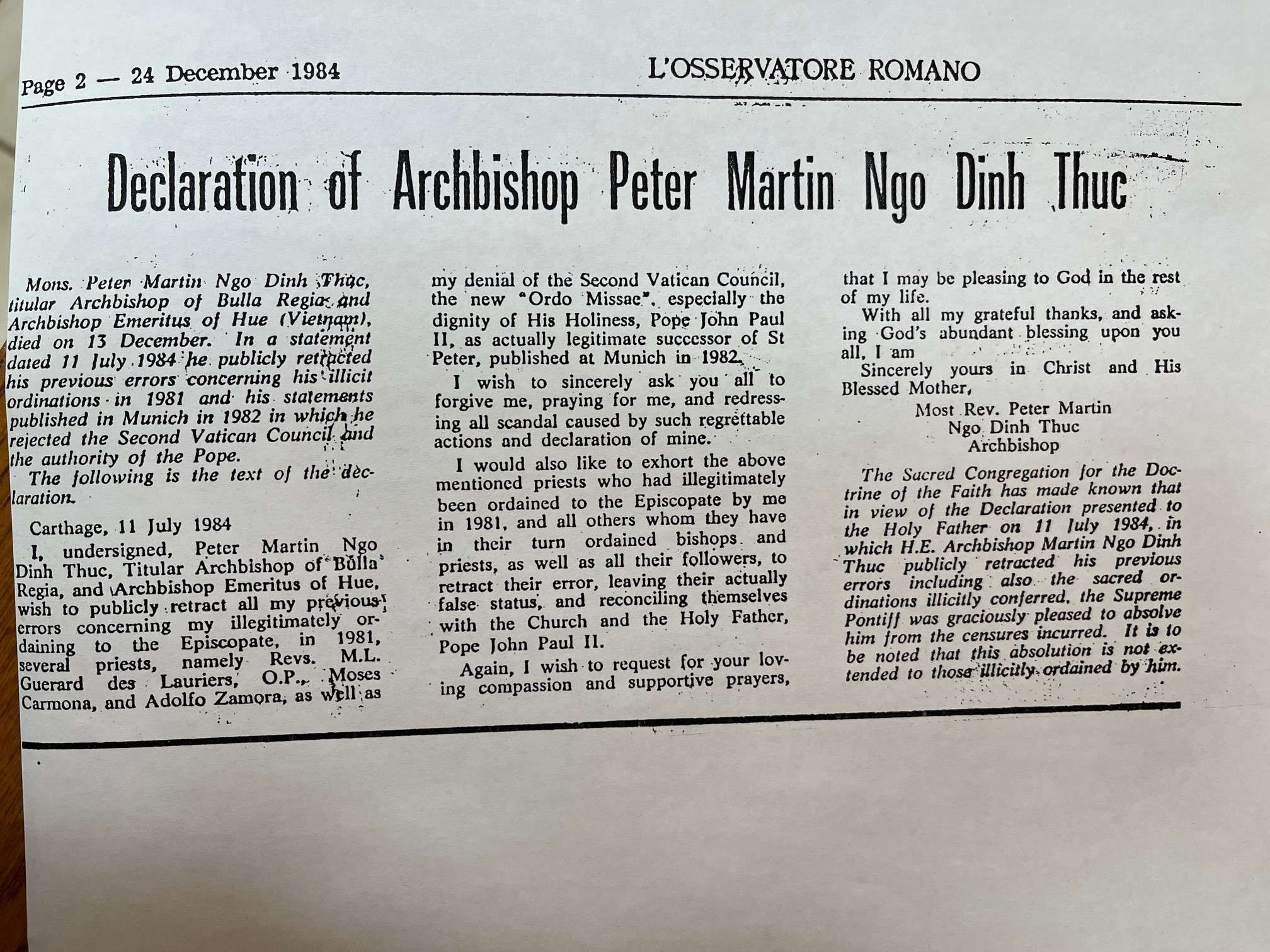

Archbishop Thục did not consecrate bishops specifically to promote sedevacantism. After his consecration of Bishop Carmona, he reconciled with The Vatican and expressed regret for his unauthorized consecrations. He celebrated the post-Vatican II Mass in the months before his death in 1984 and requested that everyone return to the Catholic Church under Pope John Paul II. Various groups utilized Thục to obtain what they considered valid apostolic succession and then pursued their own theological directions.

In the early 1980s, Thục was living in upstate New York until Vietnamese Catholic priests from Missouri arranged for him to relocate to the Vietnamese Catholic community in Carthage, Missouri, where he died in 1984.

The CMRI's presentation of Archbishop Thục's later years (1975-1984) focuses primarily on questions of validity while giving less attention to his various consecrations and final reconciliation with Rome.

Sedevacantist Focus on Validity

The CMRI emphasizes the validity of Archbishop Thục's consecrations and his episcopal credentials while minimizing discussion of his other activities or the various groups that derive orders from him. CMRI educational materials teach the concept of "ex opere operato" to focus attention on validity rather than on the circumstances or motivations surrounding the consecrations.

This approach treats consecrations as primarily sacramental acts whose effectiveness depends on proper form and intention rather than on canonical authorization or the subsequent behavior of the participants. Critics note that this perspective minimizes questions about the appropriateness or legitimacy of unauthorized episcopal actions.

Palmarian Church Consecrations

Magnus Lundberg at Uppsala University has written extensively about the Palmarian Church and provides news coverage on his website.

- A Pope of their Own (Second Edition) by Magnus Lundberg (2020) (direct download)

- Magnus Lundberg's Palmarian Page

Prior to his involvement with sedevacantist groups, Archbishop Thục consecrated Clemente Dominguez y Gomez and four others in the Spanish town of El Palmar de Troya. The Palmarian bishops subsequently founded the Palmarian Church and declared that the papacy had been mystically transferred from Rome to El Palmar de Troya. The group remained largely unknown to most traditionalist Catholics until they began publishing videos on YouTube in recent years.

Additional Consecrations (1975-1982)

Over approximately six years, Bishop Thục consecrated 15 individuals: 5 for the Palmarian Church, 5 for Old Catholic groups, and 5 for various sedevacantist organizations. The timeline and circumstances of these consecrations raise questions about Thục's motivations and consistency.

Key events include:

- December 31, 1975: Ordained five men to priesthood for Palmar de Troya group

- January 11, 1976: Consecrated five men to episcopacy for the same group

- September 17, 1976: Paul VI excommunicated Thục, who subsequently recanted

- 1977-1978: Consecrated multiple bishops for Old Catholic groups

- April 16, 1981: Documented concelebrating the New Mass with Bishop Barthe de Frejus

- May 7, 1981: Consecrated Guerard des Lauriers (three weeks after the New Mass incident)

- October 17, 1981: Consecrated Mexican bishops Moises Carmona and Adolfo Zamora

- 1982: Consecrated additional traditionalist bishops Luigi Boni and Christian Datessen

- March 12, 1983: John Paul II excommunicated Thục for unauthorized consecrations

- January 8, 1984: Thục moved to Vietnamese seminary in Carthage, Missouri

Final Years in Carthage, Missouri

This section includes material from Tuan Hoang at Pepperdine University. Bishop Thục reconciled with The Vatican before his death in 1984 and was celebrating the Mass of Paul VI while living at the Vietnamese CMC community in Carthage, Missouri.

In 1982, Thục was invited by a schismatic group of Franciscans in Rochester, NY, led by Louis Vezelis. After Vietnamese Catholic priests learned of his presence in New York, they organized his relocation to the Vietnamese Catholic community in Missouri.

Around lunar New Year 1984, Fr. Điển flew to New York and convinced Thục to accompany him to Washington, DC, ostensibly for a Vietnamese New Year celebration. The group actually proceeded to the Apostolic Nunciature of the Holy See. Bishop Vezelis had sent a bodyguard with Thục, and both sides disputed custody. Police declared that Thục had the right to choose his residence, and he chose the Vietnamese community and Roman Church.

Seven months later, Thục celebrated Mass before thousands of Vietnamese Catholics. Four months after that celebration, he died in the care of the Congregation of the Mother of the Redeemer (CMC) in Carthage.

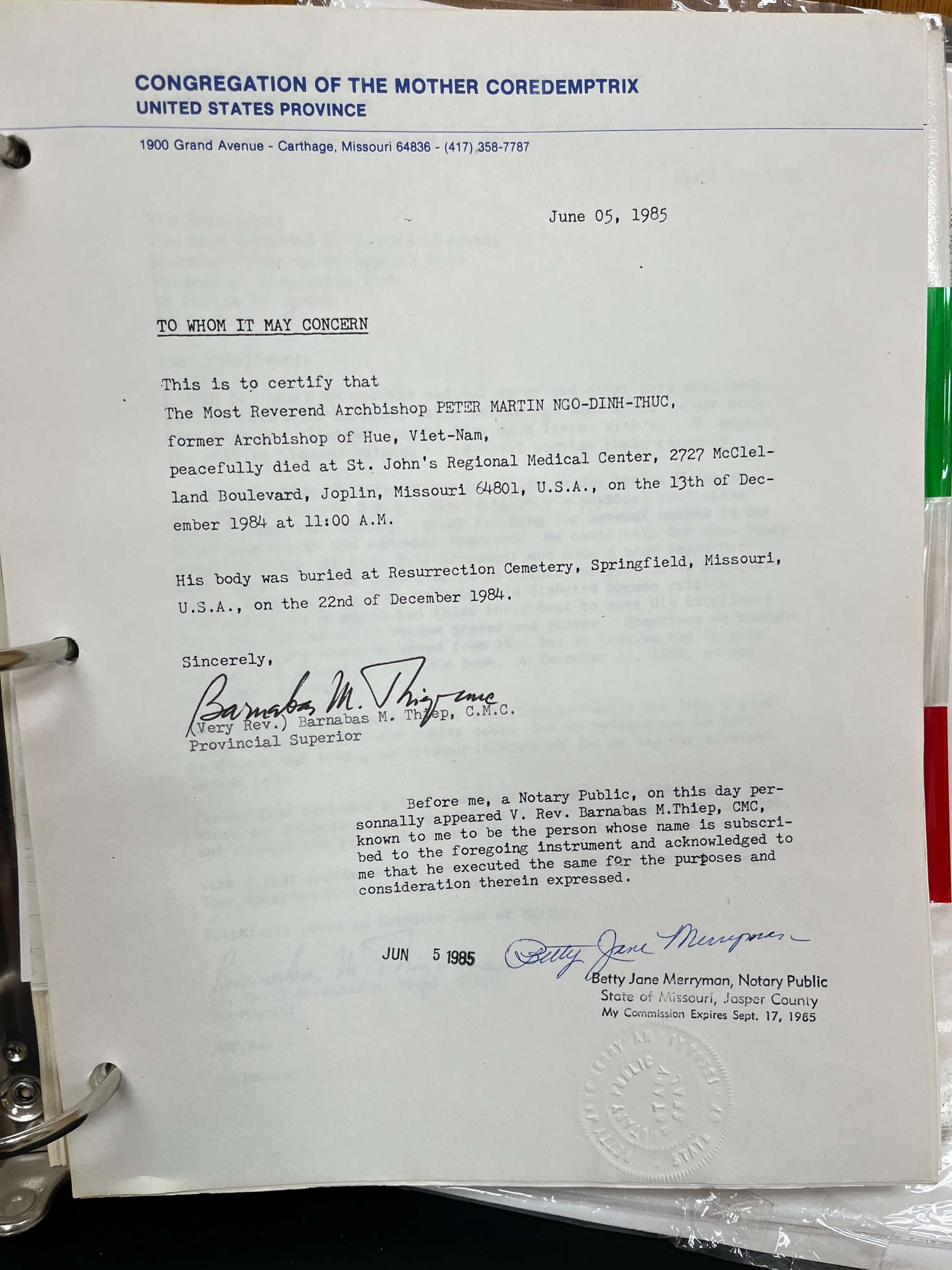

Death and Burial

Archbishop Thục died at St. John's Regional Medical Center in Joplin, Missouri on December 13, 1984, and was buried at Resurrection Cemetery in Springfield, Missouri on December 22, 1984. In 2016, his remains, along with those of other priests and brothers, were transferred to Park Cemetery (801 S Baker Blvd, 417-358-4534) in Carthage, Missouri.

CMC Death Notice: June 5, 1985

This letter from the CMC documented the death of Archbishop Thục.

1984 Declaration of Reconciliation

In this article published in L'Osservatore Romano, Archbishop Thục expressed regret and retracted his previous unauthorized consecrations. The CMRI has questioned its authenticity or minimized its importance, arguing that the consecrations remained valid regardless of Thục's later change of position.

CMRI Relationships with Thục Bishops

Bishop George Musey (1985-1986)

The CMRI first established a relationship with Bishop George Musey in 1985. In September 1986, Bishop Musey left the organization following disagreements, taking 35 families (approximately 100 people) and some CMRI nuns with him.

Bishop George Musey (1928—1992) was the son of George Musey Sr. (1900—1935), also known as "one-armed George Musey," who was an organized crime figure in Galveston, Texas, during the Prohibition era. Musey Sr. led the Downtown Gang until his assassination by rival organized crime groups in the early 1930s.

Bishop Robert McKenna (1987-1989)

After Bishop Musey's departure, the CMRI established a relationship with Bishop Robert McKenna. Like Bishop Musey, he departed following conflicts with the organization.

Bishop Moisés Carmona (1991)

The CMRI found a bishop willing to consecrate one of their own priests when Bishop Mark Pivarunas was consecrated by Bishop Carmona in 1991. Thirty-eight days after the consecration, Bishop Carmona died in a car accident.

Political and Personal Motivations

Thục's behavior from 1975 to 1984 can be understood within the context of Vietnamese Catholic political culture and the Ngo family's approach to power. American sedevacantists may not fully understand this background when interpreting his actions.

Thuc consistently made calculated decisions rather than acting from confusion or senility. Explanations involving "old age" or mental incapacity were likely strategic covers rather than accurate descriptions of his mental state.

Thục had sought independence from Roman administrative control even before the 1960s. He maintained loyalty to Catholic doctrine while resisting Vatican authority over Vietnamese Catholic practices and administration. This position was adapted by American sedevacantists for their own organizational purposes.

Similar to organized crime family structures, Thục's primary loyalty was to his family. His conflicts with other bishops often stemmed from their opposition to Ngo family political interests rather than purely theological disagreements.

After the fall of Saigon in 1975, when Thục realized he would never return to power in Vietnam, he changed tactics to gain influence and resources through other means. The timing of his consecrations, beginning shortly after the Fall of Saigon, supports this interpretation.